What to do when Jaws shows up in the chum slick.

Story and photos by Michael Love Jr.

We were three old college roommates, now consumed with fly fishing, meeting in San Diego to get our fix. On the first afternoon with On the Fly Charters, we whipped Clousers into Mission Bay and hooked up with some barred and spotted sand bass. But our sights were set higher; over the next two days, we would target the real dramatis personae of the area-the shortfin mako, which roams the Pacific off San Diego from June through October. And while doing so, we’d get a real toothy surprise. The Southern California Bight stretches from Point Conception to San Diego and serves as a transition zone between two North Pacific water masses, the Pacific equatorial and Pacific subarctic. The area is one of three known mako rookeries; the others are off New Zealand and Madagascar. The area also draws other sharks, as we soon discovered.

Capt. Dave Trimble owns On the Fly Charters. His group of guides maintains 12- to 16-weight fly rods with heavy tippet, wire leaders, and flies that Trimble ties. Once on the water, Trimble made an analysis of the water temperature, current and wind, and pointed the bow toward what he called “sharky water:’

Adrift on the blue, we dropped chum, forming our “burley slick:’ This was a· sight-fishing game, and for 45 minutes we stared at the slick, barely blinking. Then it came-70 pounds of sleek blue.

John Hedgpeth was the first to step up, graciously getting our first nervous mistakes out of the way. There they were-poor casts and missed hooksets, all in full focus. But then he put it together and sank the steel into that mako, which immediately showed off its airborne skills. Once we got that fish to the boat and removed the hook, the action was almost nonstop, with the mal,os coming in one after the other. Makos are the fastest sharks on the planet, and the highest leapers, and our reels screamed. Our lines tore rooster tails across the surface as these sharks fought against our lines and hooks. Trimble soon said we’d hit the best bite he’d seen in a long time, and by 1:30 p.m., we’d already landed 12 makos ranging between 40 and 90 pounds.

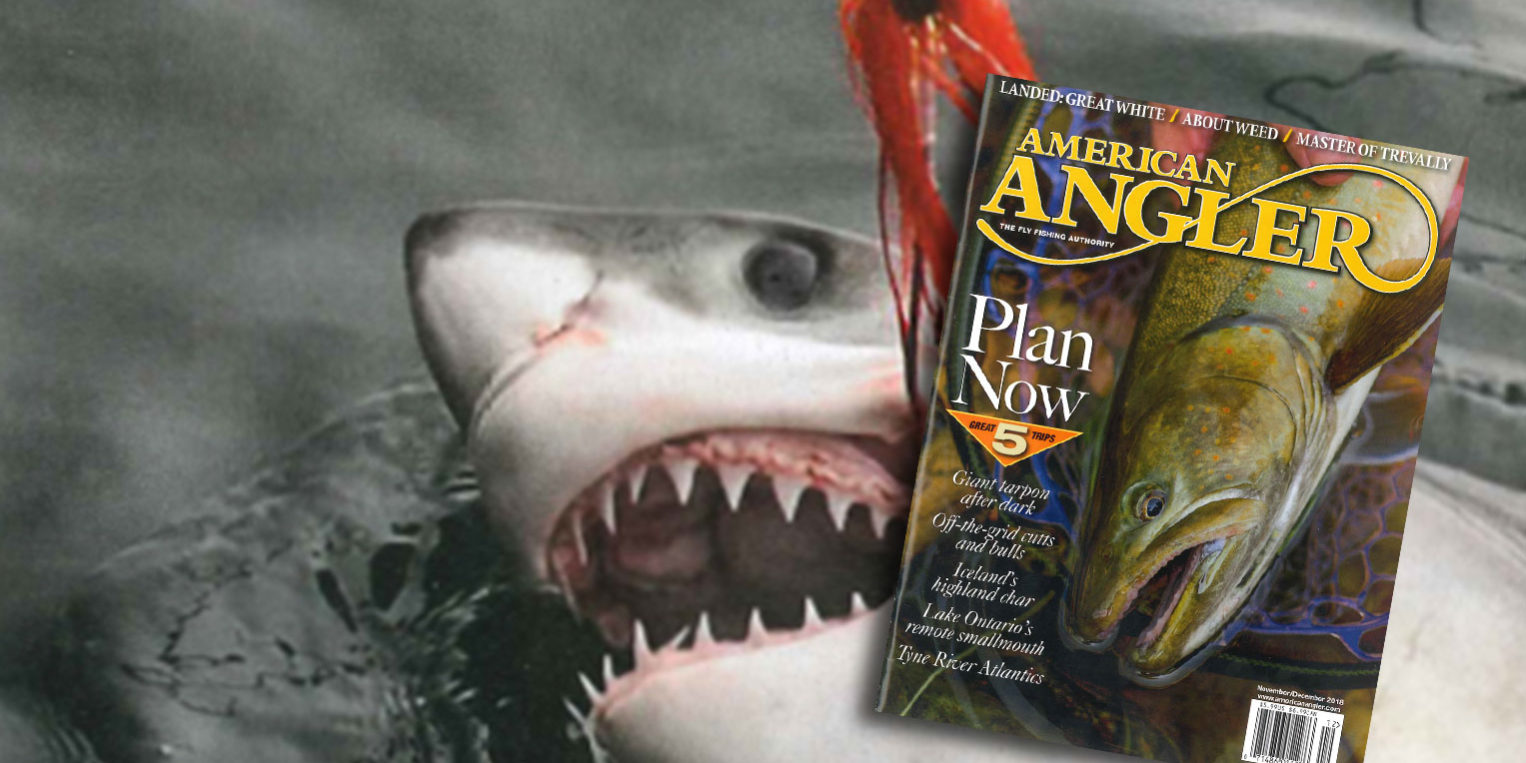

During a 15-minute lull, I practiced casting. And while I was doing so, Trimble saw a dark form move through the chum line. As my fly sank, Trimble said, “Set the hook.” I did and the reel screamed. I noticed that this fish was darker than the makos we’d caught, and 20 minutes into the fight, Trimble verified that observation, saying, “Homie, I think you got a great white shark!”

The great white fought differently from the makos. It made quick runs and thrashed the surface. It didn’t dive much and, unlike the makos, did not jump. Its speed didn’t match the makos’ either, but it proved to have an advantage in stamina during a steady 15 minutes of fight. We fought the fish as quickly as possible, as Trimble was immensely concerned about a quick release and the health of the fish. It is, in fact, illegal to fish or possess a great white. Faced with this one’s volunteerism, it seemed sensible to land and release it as gently as possible. That meant bringing it to the boat to remove the massive steel hook with a long dehooker. The shark was a “pup” of around 100 pounds; we couldn’t determine its sex. Trimble hears of great white sightings every few years, but he assured us this encounter was extremely rare.

Soon after releasing the shark, there was buzz on the radio, and by the time we hit the dock, news of the great whiteperhaps only the third ever caught on fly gear-had spread widely. Apparently, I’d hit the jackpot of California shark fishing without even knowing it. One of the mates leaned to my ear and said, “You ought to buy yourself a lottery ticket. You’ll never have a luckier day.”

But the following day served up equal surprise, despite a big change in the weather. A nervous wind had arrived, and a dense fog blanketed the marina. Still, the bite was red hot, and by midday we’d landed and released 12 makos.

Over two days, Trimble told us many stories, foremost a tale of a huge mako that he called Big Mo. And then it showed up, with a huge triangular fin cutting through the chum.

Trimble shouted, “That’s Big Mo, boys! She’s eight hundred pounds if she’s an ounce.” She was almost 10 times the size of any shark we’d seen. She circled the boat repeatedly, and Trimble drew her close with a teaser fly. Then Todd H’doubler stepped forward and somehow made a perfect cast, landing the fly right at her nose. She took the fly and H’doubler set the hook. With the fish on the line, Trimble gunned the engines; mako have no fear of boats and can launch right onto the deck. He wanted to put some distance between us and that fresh fish. And it’s a good thing he did; she launched 12 feet high, six times.

I noticed that just behind us were the rolling hills of Torrey Pines, home of the PGA Tour’s Farmers Insurance Open and the 2008 US Open. The view of Big Mo doin’ her thing gave those boys on the links a whole new meaning for the term water hazard.

After an hour-long fight, we brought Big Mo as close as we dared, then popped the leader from a barbless hook. Sweat poured off H’doubler, and his hands shook.

The denouement stood at a two-day total of 28 makos and one great white. It’s strictly catch-and-release on these beasts, and all our fish were released in good shape. While shark fishing may not be on the top of most fly fishers’ hit lists, makos are great sport-and I can tell you it’s a special moment to have one on the end of a line.

Note: Riley Love assisted with the writing of this article.

Love, Riley / Michael Riley Jr. “Beast Mode.” American Angler. November/December 2018